I was on a panel the other week where we talked about ‘Cultivating a Product-Centric Culture’.

One of the questions was about what a Product-centric or product-led culture is and looks like?

This got me thinking a bit about trying to codify it — beyond the “it’s about being customer-centric…” and other generic statements.

And perhaps the best place to start is to talk about what it is not.

What Product-centric companies are not…

My friends and fellow panellists were quick to talk about what it is not, and I think it’s probably easiest to start here too.

It’s not:

- Product Management-led

- Product Managers are the boss

- Where product makes all the calls

- Something that only engineering and product do

- Doing 12-week long discovery

- Do only what our customers want us to do

What Product-centric companies share

Thinking about codifying this further, I thought about some of the common attributes — common norms — that I’ve observed in product-led companies.

They all:

- Think in terms of products, not projects

- Invest into their products and services as a strategic enabler (not a cost centre)

- Experiment and don’t assume they have all the answers or are always right

- Regularly talk to and about their customers

- Use data to inform decisions, strategies, priorities, etc

- Allow the best ideas to win based on evidence and supporting data/research

- Focus on impact. They don’t fuss about output, velocity, etc… rather they obsess about the outcomes (customer and business impacts)

- See product success as a company effort— not something product-tech does. Everyone has their part and role to play towards product success.

This is in contrast to companies that:

- Think in terms of projects and deliverables

- See their products as a cost-centre. Operating expenses that they need to minimise

- See discovery and experimentation as a waste of time — “we know what our customers need”

- Rarely or never speak to their customers

- Don’t have a robust way to make decisions.

- Have little to no data at all. And if they did they don’t use it.

- Fuss over metrics like velocity, timelines, etc.

- Views product as something that Product Managers do. The company is often siloed as a result — “I’m an engineer, I don’t care about why…just tell me what to build”

Why are companies becoming Product-led?

Today we can purchase groceries without ever leaving our home. Order food that arrives at your doorstep.

You can even hail a taxi and know precisely when it will arrive, how much it will cost and how long it’ll take. When the car arrives, the driver will know your name and final destination. Upon arrival, there is no need to exchange payments or any nasty fee surprises. Instead, you hop out swiftly and carry on with your journey.

These types of experiences are fast becoming the norm.

Companies have leveraged a different mindset, a different way of thinking and running a business to create these competitive experiences.

Although some of these experiences may not be in your industry, your customers aren’t bound by an industry. They experience a whole suite of experiences every day and the best will always stand out and be compared to the worst, regardless of what industry they were in.

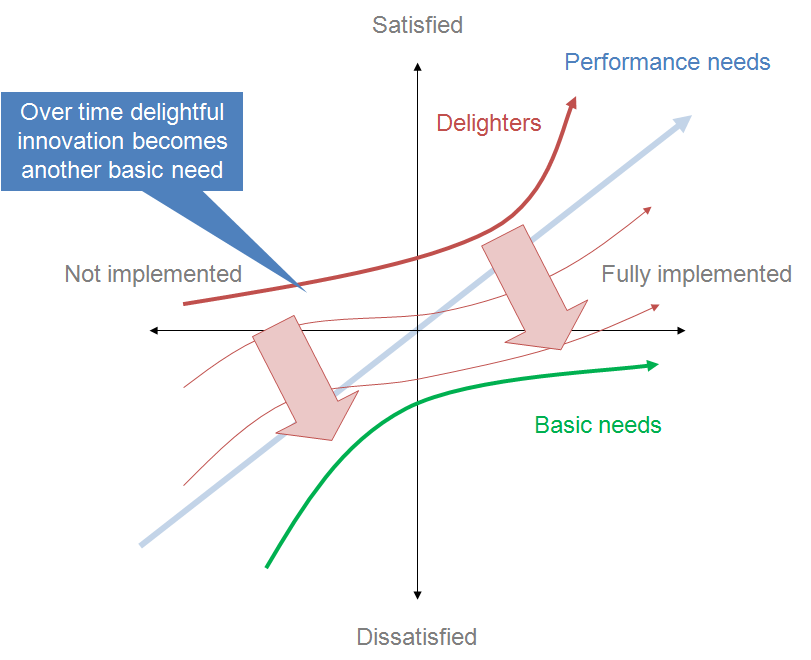

As the Kano Model illustrates, once delightful experiences will over time degrade and become a base expectation.

Internet access on our mobile devices was once unique but now expected. Accepting Apple Pay, fast loading webpages, online self-service, chat support, etc are all examples of experiences that were once innovative but are now a base expectation.

Unfortunately, a study done by Qualitics found that 80% of CEOs of fortune 100 companies in the United States believe they are delivering a superior experience, whilst only an average of 8% of their customers agreed.

Digitization has also brought unparalleled levels of competition. It has also made it easier than ever for customers to switch between providers.

The need to continually improve your products and services to deliver a high-quality experience is more paramount than ever.

Products vs Projects

Projects are finite. They have a start and end date.

They also require fixing scope, time and resources. Doing so results in projects being primarily measured by their ability to deliver an agreed scope by a certain timeframe.

However, whilst much of this is necessary, the project mentality focuses too heavily on fixing output and often neglects the outcomes that we are trying to achieve.

Delivering a specific scope on time and on a budget is great, but there is no guarantee that it will lead to a positive business or customer outcome.

Shipping a new app, for example, doesn’t mean that you will suddenly acquire more customers as a result.

Product thinking, on the other hand, is not finite. There is no start or end.

Once a product exists we continue to manage, maintain and improve it over time. This ensures that we remain relevant and are delivering the right outcomes, not outputs, to the business.

This is a significant shift from the project mindset. Rather than focusing on the scope and delivery timelines, product thinking focuses on outcomes you wish to achieve. Any time constraints are not tied to scope but rather they’re aligned to an outcome.

For example, an outcome could be a ‘5% increase in new customer acquisitions by Q3 this financial year’. Meaning that we are looking to have an additional 5% of new customers by a quarter 3, and we may not achieve it with the first thing we deliver, it may be the third or fourth thing we deliver, but what we want is to achieve that outcome by Q3 this financial year.

Project Thinking

- Focuses on outputs

- Defines scope and timelines

- A clear start and end date

- Gather requirements

Vs

Product Thinking

- Focuses on outcomes

- Defines goals and objectives

- Continuous

- Conduct Research

Experimentation and Innovation

This mindset creates space for experimentation.

Because we begin with defining outcomes and goals rather than the scope there is more flexibility in what we ultimately decide to do.

In many cases, you won’t achieve the outcome on your first try, rather it may be on your third or fourth try — this is part of the innovative process — trying something, learning from it, and adapting accordingly is a key component to building digital products.

Utilizing this process with a product mindset means that we perform numerous experiments until the desired outcome is achieved.

Data-Informed

As a result, a product approach requires data to measure the outcomes and impact of what we produce.

In comparison, the primary measures in a project approach are measuring deliverable milestones against a timeline. Milestones are typically output in nature and there is no need to measure the impact or outcomes generated by the project.

It is therefore not uncommon for companies who are primarily project-centric to have little data informing their decisions because they have had little need for said data.

However, in a product approach data is vital. It’s core to decision making.

We use data in order to determine what outcomes we should be focusing on. What solutions are best to achieve that outcome and whether we ultimately hit those outcomes or not.

Data helps us understand our market and customer’s behaviours and as a result data assists us in prioritising and making sound decisions.

Customer Obsessed

The heart of why we gather data in a product approach is being customer-centric.

Customer centricity means seeking to understand your customers rather than assuming that you know what they want. This is a subtle but important mindset shift.

Customer centricity means seeking to understand your customers rather than assuming that you know what they want. This is a subtle but important mindset shift.

In a project approach, we often come up with an idea, we then go into requirements gathering and define what we would need to do in order to deliver it. Once defined we begin to execute on the idea and finally we deliver it to our customers.

Throughout this entire approach, there is little-to-no interaction with actual customers. As a result, we make a large number of assumptions about our customers, their needs and behaviours that add risk to the success of the idea.

Rather, in a product approach, we seek to validate our assumptions rather than assuming we know what our customers need. This is often achieved through customer interviews, co-creation workshops and analysing data.

Conclusion: It’s not all ‘rainbows and roses’

Something that I’ve thought a lot about recently is that we can sometimes be our own worst enemies in the product space.

We regularly talk about how the ‘best work’ and many of us aren’t working at these sorts of companies.

Now it’s super important and valuable to understand how the best work however for many, we can find ourselves disappointed when we join a company that falls short of that image.

I’m sure there are some of you that read this article and thought — “I wish I could work in a place like that!”

You’re not alone.

As a coach and consultant, I have the privilege of seeing how many different companies operate and nowhere is perfect.

Even in places that sit closer to the ‘product-led’ end of the spectrum will still have occasions where you’re doing work for investors or the founder, or where you don’t have the luxury of time to do in-depth discovery and research, instead you just need to “ship it”.

Further different industries will also look different.

For example, a highly regulated space, like the medical industry may mean more controlled experimentation, more checks-and-balances, and longer release cycles. And the notion of heavy sales cycles in the B2B space may mean doing things for sales/buyers that have little value to end-users — but that’s ok.

The notion of being 100% empowered as a Product Manager is a fallacy. We don’t operate in a vacuum. We will regularly find ourselves needing to balance things and product-led companies are no different.

In fact, I don’t like using the term — empowered — because it can mean many different things — “empowered to do what?”

Nowhere is perfect but we can bring things back to first principles.

If you can:

- rationalise a direction with data,

- speak with your customers regularly

- view products as strategic enablers, not a cost centre

- frequently run experiments

- etc

Then you’re on the right side of the equation of being product-led.